- Home

- Whitney Way Thore

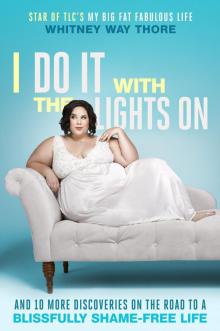

I Do It with the Lights On Page 9

I Do It with the Lights On Read online

Page 9

Today, I get criticized often for talking about PCOS. I hear multiple times a day that PCOS isn’t even a real disorder or that I must be using it as an excuse because “I/my sister/wife/brother’s ex-girlfriend has it and SHE isn’t as fat as you.” Dealing with misinformed people like this is exhausting.

PCOS made me fat. The inability of insulin to function normally is one reason why women with PCOS tend to gain weight or have a hard time losing weight.*2

Did it make me this fat? No, I can’t say that, but it’s not as easy as attributing the first hundred pounds to PCOS and then saying I did all the rest, either. Because insulin resistance complicates my body in ways that will not affect a person without insulin resistance, it will always be significantly easier for me to gain weight and harder for me to lose it regardless of what I do. Can I pinpoint the exact biological processes that caused the rolls on my back or the flab on my arms? Of course not—and, no, the pizza didn’t help matters. But I want to be able to bring attention to this disorder that affects millions of women worldwide without being blasted for “making excuses.” Because the truth is, I don’t care why anyone is fat, and I don’t feel that I need an excuse to exist in my body the way it is now; but I also have a responsibility, as a woman suffering from an underrepresented incurable syndrome, to talk about it and make people listen.

* * *

*1 health.usnews.com/health-news/patient-advice/articles/2015/07/27/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-the-silent-disorder-that-wreaks-havoc-on-the-body

*2 www.obesityaction.org/educational-resources/resource-articles-2/obesity-related-diseases/polycystic-ovarian-syndrome-pcos-and-obesity

6

AMERICANS AREN’T THE WORST OF THE FAT-SHAMERS

As I slowly came to terms with my PCOS diagnosis, I began to find my footing once again, and after graduating from college, Eric and I decided to take an adventurous next step. A friend of ours named Daryl from the theatre department had left the year before to teach English in Korea, and without any better future plans, Eric and I armed ourselves with a Lonely Planet guide and we booked our tickets to do the same. Immediately after landing in Daegu, South Korea, I experienced major sensory overload. The city was an overwhelming landscape of sky-high apartment buildings, brightly lit digital screens, and restaurants sandwiched between shops and PC Bangs (gaming rooms). The sidewalks were crowded with throngs of people, looking like giant, moving amoebas made up of suits, high heels, and school uniforms. Taxis, buses, and cars honked incessantly. My comparatively small-town upbringing had not prepared me for all of the pulsating excitement of urban life, and all the auditory and visual diversions made simply crossing the street could spark a panic attack.

Adding to my general bafflement was the fact that Eric and I did not speak one word of Korean. We didn’t know our physical address and we didn’t even have a cellphone (this was before iPhones existed). But the most unnerving thing was that in this bustling metropolis of more than 2.5 million citizens, we knew only one person: our college friend, Daryl. I’d done my fair share of traveling in Europe by this point, but knowing that I was not a tourist with a hotel reservation and a ticket back home was discombobulating.

Eric and I began our training at MoonKkang English School, which had eighteen different branches scattered throughout the country. Because MoonKkang was a hagwon (“academy” is the closest English translation), students attended after their regular school day between four-thirty and ten-thirty P.M., spending one hour with a foreign teacher and one hour with a Korean counterpart. Students were not allowed to speak Korean in English class, nor were we allowed to speak it to them. The thought of leaving school only to attend more school seemed like overkill to me, but this was the norm in Korea, and children often attended two or three different types of academies each day. There were three levels of schools within the MoonKkang system: regular, special, and Young Jae, which my managers described as the “genius school.” Since Eric and I would be teaching at a regular branch, the ability to discipline a roomful of rambunctious children whose language we didn’t understand would prove more useful than any English expertise.

Our training also doubled as a crash course in cultural sensitivity. We learned never to use the color red to write a student’s name on the white board (red is reserved for writing names of the deceased); we were shown how to motion for a student with our palm turned down instead of up (the latter is meant for calling a dog); and we were advised to always use two hands when passing something to an elder or someone in a higher position than ourselves.

Life abroad presented some minor inconveniences, mostly related to lack of appliances—our apartment had no dishwasher, dryer, or garbage disposal, so we cleaned up after meals the old-fashioned way, hung our clothes up to dry, and composted leftover food. We had a toilet, but many places, including our school, didn’t. Instead, it had squatters—porcelain bowls set into the floor—and toilet paper was not to be flushed, but placed in a small trash can within each stall. Maneuvering my 280-pound body into a crouched position and hovering over a squatter for the duration of my bathroom experience involved a learning curve that my quads did not appreciate.

There were things that made me scratch my head, like the inability (or unwillingness, I wasn’t sure which) to line up at the ATM or cash register, the puzzling promotional deals like “Buy one lipstick, get a pack of men’s underwear for free,” how Koreans are considered one year old at birth and everyone turns a year older on January 1 (making a child born in December two years old just one month after they are born), and, perhaps the most disconcerting thing of all, corn on pizza. But for every instance of something I found bizarre, there was something else that I thought was genius, like floor heating, twenty-four-hour delivery for practically everything (even fast food), and televisions at the dentist’s office. Koreans flat-out had the best customer service I’d ever experienced and the cleanest subway stations I’d ever set foot in, along with some of the most sophisticated technology, like the fastest high-speed Internet in the world and high-speed trains I’d never seen the likes of in North America. I even grew to find some of the initially peculiar things endearing, like the way couples wore matching shirts, the way people ate communally, and how hand-holding between friends was normal, regardless of age or gender.

But for all of the positives, there were some striking differences that I couldn’t reconcile. For starters, South Korea has a heavy drinking culture, and it was commonplace every morning of the week to stumble over a man passed out on the street curled up in a drunken stupor, still dressed in his suit, spooning with his briefcase. No one seemed to blink when a sloshed man unzipped his pants to relieve himself at a busy crosswalk, shooting urine onto the concrete and narrowly missing pedestrians. Twice I found myself on the street witnessing an inebriated man beating his wife or girlfriend in front of dozens of people who remained unfazed.

And for all of Korea’s innovative and progressive leadership in technology, I found the country to be archaic in other ways. Korea was not only extremely ethnocentric, but at times, xenophobic. When Daryl—who is black—and I walked on the streets together, people called out, “Ah-free-ka!” (Africa!) I was shocked one night when I was flipping through channels on the TV and landed on a show featuring Korean performers wearing blackface. My colleagues and students alike regularly spoke ill of the Japanese, and asked me why anyone would want to vacation in “dirty” countries like Vietnam or the Philippines. After a couple of weeks in the country, my parents sent me a care package, and in it was a beautiful, diamond-encrusted heart pendant. My coworker oohed and awed over it, then turned the box over in her hand and gasped. “Oh! Too bad,” she giggled, pointing to the small writing on the bottom of the box. “Never mind. It’s made in China.”

I knew before arriving that Koreans were generally quite slim and that I wouldn’t be able to purchase any clothes there. One of my first Korean friends was the equivalent of a U.S. size 14 and she bashfully confided i

n me that she had to shop for men’s clothes to find anything that fit her body and that her mother harangued her to lose weight so she could find a husband. Signs and advertisements displaying the country’s obsession with plastic surgery were everywhere, broadcasting a belief that anything could (and should) be cosmetically fixed to fit the preferred aesthetic. Beauty standards were different and even more rigid than back home—Koreans wanted pale skin (it was difficult to find makeup or sunscreen without lightening or whitening agents), creased eyelids (many of my teenage students already had “double eyelid” surgery), and slender bodies with an “S-curve” for women.

Despite these unpleasant attributes, Eric and I were determined to make it our home, so we settled into our tiny apartment and bought a Persian kitten from a pet shop downtown. We named him Henry-Kimchi, a nod to Korean cuisine, and called him Henchi for short. We enrolled in hapkido (martial art) classes. I was too big to fit into any of the uniforms, but kwan jang nim (our master) brought in a seamstress to have one custom-made for me, a gesture I greatly appreciated. One day, during the trek to our dojang (training space), we encountered a gaggle of schoolchildren, laughing and whipping their miniature backpacks around.

“Annyung!” (Hello!) I greeted them as they met us, testing out my Korean. But instead of bowing or responding, as would be customary for them to do to an elder, they all began screaming, hiding their faces, and running away. That was the first time my heart broke in Korea, and I had to fight back tears as I realized that these kids were frightened of me the same way I was frightened of Frankenstein at their age. I looked like a monster to them.

As it turned out, I didn’t fare much better with adults, either. Everywhere I went, people stared at me and made no effort to conceal their reactions to my appearance. There were the passersby who slapped their chests, gasped, and pointed; the shopkeepers who rang up my items and asked, “How many kilograms?”; and a taxi driver who snorted at me for an entire mile.

A few weeks into our stint, a Canadian couple moved into the apartment above ours, and I offered to take the girl, Erin, to go get a pedicure. We slid into a taxi and had begun chatting away when the driver interrupted us. “Hamburger? Pizza? You like?” Thinking he was just making conversation, we answered, “Oh, yes, delicious,” and went back to our conversation, but he continued. “No, no, no! Apples. Orang-ee!” Immediately, it dawned on me that he was trying to give me diet advice, and I didn’t want to be humiliated like I was by the last taxi driver, who had made pig noises at me while I sat there powerless, trapped in his backseat.

“Yogiyo,” I said. (Stop here, please.) He looked confused, but he took his foot off of the accelerator. “Yogiyo,” I repeated, this time more firmly. Finally, he stopped the taxi and pulled over, trying to communicate that we were still several blocks from our destination. “Gwen-chan-ayo” (It’s okay.) I replied, as I paid him and stepped out. Erin initially looked confused, but had now caught on, and she linked her arm in mine. “I don’t mind walking the rest of the way,” she said. “I need the exercise anyway.”

Having to deal with the rudeness of strangers wasn’t easy, to say the least, but I resolved to make the best of it and remain optimistic about the experience. I knew I was the largest person many Koreans had ever seen in real life, and this would naturally provoke a reaction, so I tried to ignore it as best I could. The hours I spent teaching at MoonKkang helped, and I immersed myself into my new job, realizing that I truly loved it. Even though my students spoke mostly beginner English (and low-level intermediate at best), sometimes they hit me with unexpected wisdom. One day I was making conversation with them and asked if they thought North Korea and South Korea should reunite. A student who had never spoken a full sentence in English raised his hand, and with a solemn face, answered, “We have to, Teacher. One family cannot live in two houses.”

Not long after that, in the same class, we read an article that detailed the side effects of obesity. The article outlined health problems like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. After we read it aloud, the students turned their papers over, and prepared for the comprehension questions.

“So,” I asked, “what is one side effect of obesity?” A quiet, attentive student who went by the name Kerrick raised his hand.

With stone-cold seriousness he answered, “Suicide.”

His answer caught me so off guard that I laughed inappropriately. “Well, no…” I began. “The article doesn’t mention that. I’m obese, right?”

Twelve blank faces looked back at me, nodding.

“Do you think I want to kill myself?”

Kerrick explained, “Teacher, maybe you have some depressions and maybe you want to die.”

I shook my head emphatically. “No, I promise you: I do not want to die.” I smiled wide. “I’m happy, see?”

That night when I returned home, I couldn’t stop thinking about Kerrick’s answer. I knew he wasn’t being a smart-ass, nor did he mean to be offensive. He genuinely drew the conclusion—not from the article, but from his own experiences—that obesity could lead a person so deep into depression that suicide was the only way out. I knew I wanted to address his reasoning, but I didn’t know how to effectively communicate with my students about such a sensitive, complex topic with their limited English. And I wasn’t so much stunned by Kerrick’s observation as I was saddened that it was the truth. Thousands of geographical miles apart, with more than ten years of an age difference between us—not to mention our respective contrasting cultures and customs—Kerrick and I were both living in societies that caused fat people to consider suicide as an end to their misery. I told myself that, at the very least, I could be an example of a happy fat person and maybe I’d be able to counteract the belief that fat people were all on the verge of killing themselves.

The next day I was teaching a different class, this time in my other classroom located in a corner of the building. Out of the left windows I could see a restaurant named “Beer Girls” in Konglish fashion, with the image of two Western schoolgirls and their huge breast implants leering at me. As the students were taking a few minutes to rehearse their report presentations, I heard one boy teasing his classmate.

“You should wear some lipsticks!” he shouted.

“No!” I intervened. “Hey!”

The class quieted down. I asked the student, “Why would you say she needs to wear lipstick?”

“If you are ugly, you wear lipsticks,” he replied matter-of-factly.

“No,” I said firmly, conveying my seriousness in the tone of my voice. “You do not call people ugly because you think they look different. Do you think I look different? Am I ugly? Is that a nice thing to say? Does that make me happy or sad?”

The student lowered his eyes, as he knew he was being reprimanded. It took me a while to get used to this, as Koreans who are being chastised show respect by not making eye contact.

“Every day in the street people laugh at me,” I told them, explaining that people would call me an outsider to my face. “Every day people point at me and say, ‘Waegookin!’ [Foreigner!] Every day it makes me sad.”

The child who’d been told she needed to wear lipsticks asked me, “Teacher, do you cry?”

“Yes. Sometimes I do.”

“Teacher, if ajumma (older lady) is looking at you, you should say, ‘mianhamnida,’ (I’m sorry.)” she offered.

I smiled at her, to thank her for her advice, but then Scott, one of the smartest students in the class, cleared his throat. He’d been thoughtfully listening to me and I could practically see the wheels turning in his head.

“Teacher, you should not say ‘mianhamnida’ because you are not do anything wrong!”

I let out a belly laugh. “Yes, Scott! You are right. You are so smart!” I went over to give him a high-five. Maybe there was progress to be made with these children yet.

Before I knew it a few months had passed and Eric and I used our week of vacation to go to Beijing with some other foreign teachers

. We did all the typical sightseeing things, sampled traditional Chinese food, and climbed the Great Wall. When we got back to Daegu, my managers offered me a floating teaching position, which equaled a $100-a-month raise and a lot of extra hassle, as I would be traveling to the different branches (some located in Daegu and some not) to fill in for teachers who were sick or on vacation. Even though it seemed less stable than the position I currently held, I was itching for something new to do and a way to put some space between Eric and me. Because we’d been working together in the same branch and living together for months, our relationship had become tense. Each day when we returned home from work, we ate dinner in silence. He retreated to our small extra room to play computer games and I read or wrote or clicked through the four American channels on our boxy TV until I got sleepy and went to bed alone. Eric and I hadn’t had sex in months and I thought the separation during our workday would do each of us some good. I accepted the floating position and readied myself for my first week at a branch roughly thirty minutes away.

It was a muggy, oppressive summer, and I walked several blocks to the subway station. I entered my first classroom hesitantly. The children greeted me with laughter and pointed fingers.

“Teacher. Pig-uh!” one of the students called out. “Teacher. Baby?” another asked, pointing to my stomach. “Teacher is monster!” yet another shouted, laughing hysterically.

When I dragged my weary body up my apartment steps at eleven-thirty that night, I stopped and sat on the stoop. Burying my face in my hands, I heaved a huge sigh. I realized that I’d been able to garner respect from my regular students at my old branch, but each time I walked into a classroom at a different branch, I would have to deal with the same taunts and jeers from a never-ending rotation of new children. How was I going to survive this? I called my mother, who asked me how the first day at my new job went. As much as I wanted to act like I had it all together, I couldn’t bullshit her, and the familiar comfort of her voice made me burst into tears. I told her that it was awful; it was a day full of harassment from unruly children.

I Do It with the Lights On

I Do It with the Lights On